CHAPTER ONE

THE QUESTED FAMILY BACKGROUND

ARRIVAL IN NATAL

The numbers in brackets (003) refer to the family tree and the italics were added by Cynthia as her personal relatives i.e., (Dad) being her father, etc.

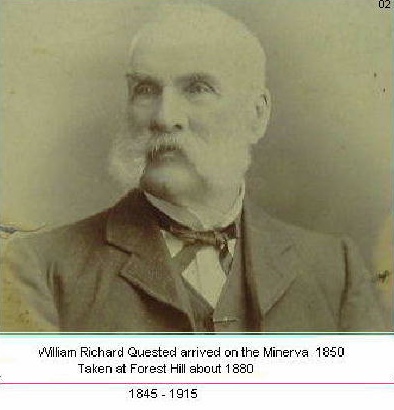

The story of the Quested family in Natal began with the arrival of the sailing ship Minerva off Port Natal on 3rd July 1850. On board were the brothers William (003) and George (253) Quested, their sisters, Harriet (348) and Caroline (354), and William’s wife Martha (004), together with her three children, William Richard (005), Harriet Susannah (172) and Frederick John.(180). The Questeds came from the County of Kent, where, in the early nineteenth century, there were a number of families bearing that name.

The story of the Quested family in Natal began with the arrival of the sailing ship Minerva off Port Natal on 3rd July 1850. On board were the brothers William (003) and George (253) Quested, their sisters, Harriet (348) and Caroline (354), and William’s wife Martha (004), together with her three children, William Richard (005), Harriet Susannah (172) and Frederick John.(180). The Questeds came from the County of Kent, where, in the early nineteenth century, there were a number of families bearing that name.

There is doubt about the origin of the name, but according to a legend which prevails amongst one family of Questeds still in Kent, the progenitor was a son of a Spanish landowner named Questelo, who, many years ago settled in England and married the daughter of a Kentish farmer. He is said to have changed his name to Quested and to have farmed at Cheriton, near Folkestone. It has been established that a long line of Questeds farmed there right up to the end of the 1930’s, the last owner of the Cheriton farm being Egerton Quested, who became well known as a breeder of Romney Marsh sheep.

Other members of the same family of Questeds claim as an inheritance of their original ancestor, that the leading male in each generation of the descendants had jet black hair, and this characteristic is said to continue even today.

Another Quested family believe their ancestors were Huguenot refugees who settled in Kent and helped to establish the textile industry which grew up in the County. The Natal Questeds also apparently believed their ancestors were Huguenot refugees from the continent.

There is evidence that a certain Augustine Quested was an incumbent at the ecclesiastical college at Wingham, not far from Canterbury, in the early 1500’s, during the reign of King Henry VIII.

Later, in the early 1600’s, Quested families held Elverton Manor and Battle Hall, both in the parish of Leeds, some five or six miles from Maidstone.

At another time the manor of Pen Court, in the parish of Hollingbourne, also only a few miles from Maidstone, was owned by a certain Mark Quested.

In the early 1800’s a Thomas Quested (001) was a captain in the Royal Marine Force, and in more recent years another Quested was Chief Constable of Hythe in Kent.

It is evident that some of the Questeds became people of consequence. A number of others were farmers and there are still Questeds farming in Kent today. Other people of the same name were blacksmiths, surveyors, inn-keepers, carpenters and labourers.

It is evident that some of the Questeds became people of consequence. A number of others were farmers and there are still Questeds farming in Kent today. Other people of the same name were blacksmiths, surveyors, inn-keepers, carpenters and labourers.

From information available, it can be stated that a number of families with the name Quested have lived in Kent since the 14th century. In the archives in the County Hall at Maidstone, there are numerous references to them in the probate indices from 1396 onwards. This shows that the name was established in the County a long time before the inflow of Huguenot refugees from France and the low countries.

One of the clan who achieved notoriety was a man named Cephas Quested, who, in the early 1800’s was the leader of a gang of smugglers or ‘Free Traders’ as they liked to call themselves, known as the ‘Aldington Gang’, which operated from the village of Aldington, about five or six miles from the coast, in the Romney Marsh area.

In those days, smuggling was a profitable activity for fishermen, longshoremen, farmers and others, all along the south coast of England, and well organised schemes were established for the transport of contraband wine, spirits, silks, tobacco and tea from landing points on the coast to destinations inland.

Once the goods had been landed by the longshoremen, after receiving their cargoes from vessels in the English Channel, armed gangs met them on shore and put up fierce resistance to any efforts by Excise men to interfere with the smuggling operations. Many running fights took place between the smugglers and the Excise men, which caused a state of feud to exist between them.

In the early 1800’s farming was at a very low ebb in Britain and unemployment was rife. Starvation stared many in the face. Hundreds of men discharged from the armed forces at the end of the Napoleonic wars failed to find jobs and had to make a living as best they could. There was no welfare state in those days. Cephas Quested was a product of his time and he, with many more like him, evidently decided that smuggling offered possibilities for getting the wherewithal to support himself and his family.

Cephas was a labourer and more or less uneducated, but had a turn for adventure. He was reputed to be a hard drinking and ruthless man, large in size, daring and reckless. Because he had an exceptional ability to see well at night, he was known to his men as ‘Night Hawk’.

It was said that Cephas Quested had a personal grudge against a particular young Excise officer, Midshipman Newton, and apparently had been heard to swear he would shoot this officer at the first opportunity, if he interfered with the gang’s activities. Newton and his men had their duty to perform, however, and that was to prevent smuggling operations and arrest smugglers as and when this was possible.

During a clash with the Aldington gang one dark and moonless night at Camber Sands, near Rye, a Midshipman McKenzie was shot and killed and several men on both sides were wounded. It was said that the fatal shot was fired by Cephas Quested, who was believed to have aimed at Midshipman Newton, but anger spoiling his aim, the shot hit the man next to Newton instead.

In the darkness the gang dispersed and got away, but on another occasion shortly afterwards, during a skirmish in the area between Lydd and Brookland, when a good deal of gunfire was exchanged, the smugglers were forced to break and run, hotly pursued by the Excise men. Two Midshipmen and several men were wounded by gunshots. On this night Midshipman Newton had disguised himself by putting on a countryman’s smock, and during the chase he managed to catch up with Quested, who, in the darkness and confusion of the moment, mistaking him for one of his own gang, thrust a musket into his hand shouting “shoot that devil Newton – I’m done and can’t go on”. Newton thereupon grabbed his man and hung on until help arrived, thereafter succeeding in getting his prisoner to jail. Cephas’s reputed good night vision quite evidently let him down on this occasion, a fact he was to pay for with his life.

In due course, Cephas Quested and an accomplice named Wraight were charged with the murder of Midshipman McKenzie. Wraight was acquitted but Quested was found guilty and sentenced to death. He was eventually hanged at Newgate Prison, London, on 4th July 1821, at the age of 32.

The trial was delayed for several months while the authorities tried to persuade Quested to turn King’s evidence, but he resolutely refused to give away the names of his confederates. Said he “No, I’ve done wrong and I'm ready to suffer for it, but I won't bring harm to others.” Because of this he became a local hero. His wife, Martha, was approached by the authorities to try and obtain from her the names of her husband’s accomplices, but having visited Cephas every week while he was in prison, and in accordance with his instructions, she divulged nothing.

At the trial, several respectable persons gave Cephas a good character and the judge, while strongly condemning the gang’s nefarious activities and the killing of Midshipman McKenzie, drew attention to Quested’s admirable spirit in remaining loyal and true to his friends, even though he was about to face death. After the execution, his widow claimed the body of her husband and took it back to Kent, sitting on the coffin during the journey by horse cart. For several days the coffin lay in the cottage at Aldington where Cephas had lived, and not only the villagers, but scores of other people from the surrounding countryside went to pay their last respects before the interment took place in the village churchyard on 8th July 1821.

In Cephas Quested’s last letter to his family before his death he wrote, “…and dear brothers, I hope this will be a warning to you and all others about there.” In spite of this warning, his cousin, James, who lived at Hawkinge, continued with his smuggling activities and was involved in a fight with the Excise men on a later occasion. He was caught, tried, convicted and sentenced to be transported as a felon to Australia. With many other fellow convicts he travelled in the ship Governor Ready in 1829. He was transported to Tasmania. There are Questeds in the Sydney area today who are possibly descended from James.

It is assumed that the remainder of the Questeds learned a lesson from these episodes and confined their further activities within the law, to more prosaic, but probably less rewarding occupations. The Questeds who came to Natal are known to have spoken on a number of occasions about their kinsmen in Kent who had taken part in smuggling operations.

While it is not known definitely where all the original Natal Questeds were born, it is apparent that they lived at various times at Stockbury and Ashford, and the County town of Maidstone, on the river Medway in Kent.

The parents of the Questeds who came to Natal in 1850 were Thomas (001)and Harriet Susannah (002) Quested, who had married on 19th July 1821. Thomas apparently died before the end of 1852 because Harriet was a widow when she came out to join her family in Natal in 1853. Just when and where Thomas died is not known, and enquiries have failed to reveal this, but it is believed he was still living in 1844 when his elder son William married Martha Ann Montforte.

Legend has it that William, George and their party had intended to emigrate to Australia, but it is assumed that their intentions were influenced by the publicity being put out at the time, proclaiming Natal to be a far more desirable country in which to settle. This was the period when Joseph Charles Byrne and a number of other emigration agents were active throughout Great Britain, stirring up interest in the possibilities of Natal, which Byrne had stated was a land where anyone could live cheaply and comfortably with very little effort. The upshot was that the Questeds came to Natal and did not go to Australia. Possibly they were influenced also by the fact that several other families from Maidstone, and thereabouts were going to Natal.

In the list of passengers on the Minerva, the brothers William and George were described as farmers, as indeed were most of the male passengers, although events were to prove that many of them had never worked on the land and knew nothing at all about farming. In fact, this description was a subterfuge in order to become an ‘approved emigrant’. Harriet was described as a milliner and Caroline as a dressmaker.

The Minerva was one of the Byrne emigrant ships, one of a number which brought some 2,000–3,000 new settlers to Natal from the British Isles during a period covering two years or so from the middle of 1849, under a scheme by which, for a payment of £10 for each person over 14 years of age, and £5 for each child, Joseph Byrne provided the necessary sea passages and guaranteed a free allocation of land, 20 acres for each full fare-paying passenger and ten acres for each child, on arrival at destination in Natal. £10 was the cost of steerage accommodation in the hold of a ship, but better accommodation was available on some of the larger vessels, at £19 intermediate and £35 cabin class. The Questeds travelled steerage.

The journey from Great Britain usually took about three months and for the majority of the passengers, especially those travelling steerage, could hardly have been an pleasant experience. Indeed, for the greater number of them the journey must have been extremely unpleasant, to say the least. The ships were essentially cargo vessels and were not designed to carry large numbers of people. The holds were overcrowded, dingy, dark and uncomfortable, and it must have been positively frightening at times, as for instance, during storms at sea, when the holds were battened down and the passengers were shut below in the bowels of the ship. The scene can be imagined. The flickering lights of candle lamps; trunks, boxes, pots and pans sliding and falling about; the crash of falling crockery, the wailing of children, the groans of frightened and seasick people, the heat and the dreadful odour of confined quarters and masses of human beings. This, combined with the creaking of the ship’s timbers, the noise of the waves crashing against the hull and the pitching and rolling of the ship must have been quite unnerving.

Toilet and sanitary arrangements on the emigrant ships were generally appalling and by all accounts the resulting stench was all-pervading. Food and water were short and of poor quality on some of the ships but, somewhat surprisingly, there were comparatively few causalities.

The Minerva, a teak built ship of 987 tons, the largest and one of the best vessels chartered by Byrne, was formerly an East India Company’s frigate. In 1850 she was owned by Messrs Manning and Anderson of London, and commanded by Captain Moir. One of the part owners of the vessel, John Laricourt Anderson, was a passenger on what was to prove its last and fatal voyage.

The Minerva sailed from London on 18th April 1850, carrying as total of 287 passengers and a large quantity of cargo. Owing to contrary winds, the ship took seven days to reach Plymouth but she left the latter port on 26th April. The Canary Islands were sighted on 8th May and the Cape Verde Islands on 14th of the month. After a reasonably good voyage of 67 days from Plymouth, and having called at Table Bay, the Minerva arrived off Port Natal on 3rd July and anchored in the outer roadstead, as was customary, to enable arrangements to be made for lighters and other small craft to come out from the Bay to take off the passengers and cargo.

In those days, and for a good many years afterwards, the larger vessels, over about 400 tons, could not enter the Bay because of the sand bar in the entrance channel. The depth of water over the bar varied considerably according to the state of the tide and weather, and the formation of the bar was affected by the Indian Ocean rollers, which kept the sand in a constant state of movement. The channel through the bar changed continually and at times only five or six feet deep. Crossing the bar was always hazardous and, in general, vessels drawing ten feet or more did not attempt to enter the Bay, even at high spring tides.

The Minerva anchored fairly close to the Conquering Hero, another emigrant ship, and one or two other vessels, in what appeared to the captain to be a safe anchorage. Later events showed that the ship was too close to the shore, and moreover, only one anchor had been dropped. This proved to be Captain Moir’s undoing.

It later transpired that the Port Captain had advised the Captain Moir to move the ship to a different position but the latter, having never been on that part of the coast before, and having never experienced the sudden changes in weather which occur off the Natal coast, did not consider any move necessary. The vessel remained, therefore, in the same position during the night of the 3rd and all day on 4th July.

About 100 passengers, mainly men, were taken off the ship during the day and landed at the Point, including Mr John Laricourt Anderson and the wife of John Moreland, Byrne’s agent in Natal. The captain returned from the shore to the ship in the evening, little expecting what was to follow during the night. Captain Moir was not the only skipper to find out by bitter experience the hazards of the Natal coast, because no fewer than 66 large vessels were blown ashore on the Durban beaches in the period 1845 to 1885.

On the night of 4th July 1850, with a strong north-easterly wind blowing and rising sea, the ship started dragging her anchor and drifting towards the shore. When this was discovered, a second anchor was dropped, but already it was too late. With a drift of some three or four knots on a strong flood tide, the strain was too great and one anchor cable broke. The other failed to hold and by this time, although the effort was made, the ship was too close to the shore to allow the crew to get the sails hoisted and the vessel headed out to sea. Thus, in the early hours of 5th July, the Minerva drifted ashore broadside on, onto a reef of rocks off the Bluff, at a spot not far from the Bay entrance, between where the South Pier is now situated, and what used to be known as Cave Rock, at the point of the Bluff.

When disaster was seen to be inevitable, the passengers were roused and assembled on the poop deck, with women and children being given shelter in the captain’s and other deck cabins. Distress signals were fired; a constant stream of rockets from the bow and stern of the ill-fated ship, according to an eye-witness on board the Henrietta, which had arrived in the vicinity that evening. The minute gun was fired to alert the authorities on shore

As can be imagined, there was great consternation amongst those on board who had been congratulating themselves on having survived the ordeals of the voyage, only to find themselves facing the prospect of death when actually within sight of their goal. A large proportion of the passengers still on board, approximately 160 of them, were women and children. The captain did his best to allay their fears and assured them that they would be landed in safety. He proved to be right in the end, but all aboard had to endure a great deal of anxiety and distress before this could be accomplished. Husbands who had gone ashore during the day and had stayed ashore that night must have suffered a great deal of mental anguish, wondering whether they would ever see their wives and children again.

Little in the way of rescue operations could be done during the hours of darkness, except to herd everybody onto the safest part of the ship, while the crew worked furiously at the chain pumps. The passengers had little time or opportunity to gather together much of their belongings, and apart from what they were wearing, most of them could only grab the smaller items which were nearest to hand to stuff into their pockets or carrier bags before they scrambled out of the holds and onto the decks.

Soon after running onto the rocks, the sea was making clean breaches over the decks, sweeping away the bulwarks and most of the ship’s boats and rigging. Under the force of the waves which pounded her against the rocky ledge just off the shore, the ship began breaking up. The rudder was forced up onto the gun deck, and soon only one mast, the main mast, remained intact. This was fortunate because from the mast, ropes were later passed ashore and fastened to large trees at the foot of the Bluff. Bonfires were made by people on shore at the Point and the Bluff to give light at the scene.

At about 3 am, a ships boat from the Henrietta approached the Minerva but it capsized in the heavy surf. Four men were pulled ashore but the second mate of the Henrietta was swept away and never seen again. He was the only casualty and it can be said that he gave his life in attempting to give aid and assistance to the shipwrecked people. The main rescue operations were started in the first light of dawn, and by the strenuous efforts of the crew and the men passengers still left on board together with scores of helpers, including those male passengers who had gone ashore the previous day, who had swarmed across the Bay to the Bluff, all of those on board the stricken vessel were got ashore by four o’clock in the afternoon without loss of life. This was done mainly by means of the one remaining ship’s boat, together with a cutter and one of Byrne’s surf boats which had been brought out on the Minerva, guided by lifelines rigged between the ship and the shore.

A few of the hardy ones got ashore by swimming and wading when the tide was low. A valuable horse, insured for £1,000, which was pushed overboard into the ocean, was swept out to sea but eventually managed to reach shore safely. Captain Moir, in the British tradition of the sea, was the last man to leave the ship.

William Quested strapped his youngest child, Freddie (180), onto his back to keep him safe during the scramble to reach dry land and thus he came to no harm. It is not known how the remainder of the family group fared during this alarming experience, except that they all survived the ordeal. It has been said the family brought two dogs with them from England and that these were got ashore without harm.

By the end of the day, the 5th July, the condition of the Minerva had worsened so much that the battered hull fell over onto her broadsides, the forepart becoming completely submerged. Within two or three days the wreck broke up altogether and soon only a few straggling timbers remained of what had once been a fine ship.

All the cargo, amounting to about 300 tons, and most of the passengers personal belongings went to the bottom of the sea in the deep water just off the Bluff. A large number of lighter items were, however, later washed ashore. For days afterwards the coastline was strewn with pieces of sodden and damaged furniture, chests of clothing and all sorts of oddments including wooden carts, wheelbarrows, ploughs, etc., and even a grand piano. Wholesale plunder took place and some of the worst offenders were said to be members of the shipwrecked crew, a number of whom got drunk on the contents of cases of liquor washed up on the beaches.

A good many articles were however, recovered and restored to their rightful owners. One young passenger, a son of Mr Ralfe, managed to salvage a barrel of beer belonging to his father. This barrel had floated ashore and a party of Africans were just about to broach it when master Ralfe laid claim to it.

It was reported that passengers were told to abandon all goods which drifted ashore because failure to do so would prejudice the insurance claim for the ship and its contents. The wise ones ignored this dubious advice and hung on to whatever of their goods they had managed to recover. Their wisdom was vindicated because no insurance compensation was ever paid to any of the passengers.

At least some of the immigrants had the satisfaction of having part of their belongings restored to them from the watery depths, and for this they must have been truly thankful. Others lost everything. A family named Russell had about £2,000 worth of agricultural equipment on board as cargo. This was entirely lost and they came ashore with the clothes they wore and a cashbox containing £50. The head of this family, the elderly Mr Russell, put on his best suit before leaving the ship, saying, that if he were fated to drown he might as well go to the bottom fittingly dressed. The Questeds lost practically everything, but managed to save a pair of sporting guns, one of which, a muzzle-loading double-barrelled shotgun, has survived the years and is now in the possession of Peter Quested, a great-grandson of William.

Among the helpers on shore during the rescue operations, one of the most outstanding was the Colonial Chaplain of Natal, the Reverend W.H.C. Lloyd. He did more than offer up prayers for those in peril on the sea! He obtained all the brandy he could lay his hands on from the military camp and used this to revive the exhausted and distressed women passengers as they were brought ashore. All the morning he, with other willing workers, waded up to their necks into the surf to carry women and children to dry land from the small boats which shuttled between the wreck and the beach. He arranged for tents from the army camp to be set up on the beach and for blankets to be supplied so as to give immediate shelter and warmth for the unfortunate new arrivals.

Other outstanding helpers were Captain Glendining of the Gem; Mr MacLeroy, who later became Government Immigration Agent; Captain Bell, the Port Captain; and John Moreland, Byrne’s agent in Natal.

The officers and men of the 45th Regiment, stationed at the Fort, and the Durban townsfolk rallied around with food and dry clothing and other necessities for the shipwrecked passengers and crew. A Minerva Relief Fund was quickly organised and generously subscribed to by the authorities and local trades-people and settlers already established, including many of the Boers who had remained in Natal after the demise of their short-lived Republic of Natalia. The Boers were said to have shown great kindness and hospitality to newly arrived British settlers.

After the wreck there was much talk about the cause of the Minerva’s loss and suggestions that the grounding was deliberately planned. On the night of the disaster a passenger from Hull was said to have told the ship’s mate, at eight o’clock in the evening, that he was sure the ship was dragging her anchor, but the mate apparently replied that it was none of this passenger’s business, and that he was to go below immediately. However, at about 11 o’clock the same passenger was said to have gone up to the deck and to have seen that the ship was indeed drifting, but he could see nothing being done about it. This caused him to think the ship was deliberately being put to hazard and, because of this, he did not take off his clothes or go to bed that night.

If this story is true there is little doubt that he must have told others about his fears, but so far as can be ascertained, no mention of this suspicion was made at the official enquiry into the loss of the ship. On the other hand a number of the survivors later signed a memorial addressed to Captain Moir, thanking him for all he had done to ensure the safety of his passengers during the period of crisis.

Among the fellow passengers of the Questeds on the Minerva were the following:

Mr Walter (clergyman) & family Edward S. Stafford

Hugh Browne John Whipp

William Cowley & family The Russell family (7)

R. Ralfe & family (4 sons) John Wade (schoolmaster) & family

R.R. Riley William Walsh & family

George Gain W.M. Ford & family

Abraham Nickson William Jefferies & family

William Skinner Mr & Mrs James McKenzie

Samuel Williams Frederick & William Simpson

Mr & Mrs John Anderson Mr & Mrs George McLeod

Mr & Mrs Isaac Finnemore William Bartholomew

B. Harrington John Day

Adam Hulton W.R. Deane

F. Lawrence Thomas Dobson

John Mead Alfred M. Goulden

George Metcalfe Samuel Grant

Frederick W. More George Hall

Thomas Pearson Thomas Hammond

John Potterill John Prince

Robert Ratsey The Bailey family

The Watson family Mrs Moreland (wife of Byrne’s agent

(see Siedle/Watson family tree) in Natal)

(Mary Watson married Otto Siedle, her sister Ethel married Felix Hollander Mayor of Durban 1930’s)

The list is incomplete, but some of the above names have become very well known in Natal and history has shown that in spite of a disheartening start to their lives in a new country, many of the Minerva emigrants achieved considerable success in the years that followed.