CHAPTER THREE

SUGAR PLANTING

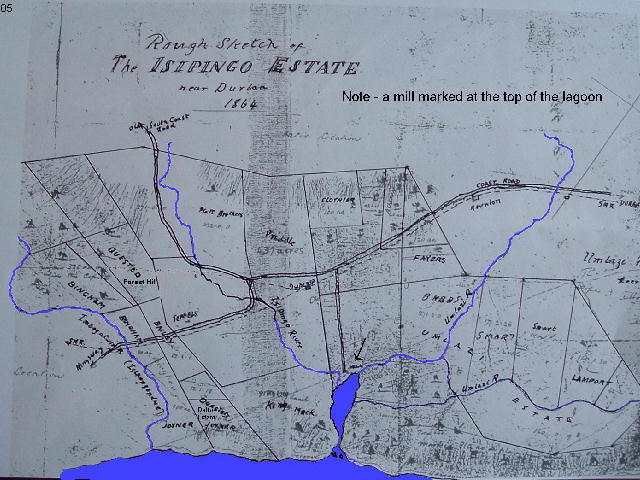

Dick King, that famous character in Natal history, had occupied a farm at Isipingo from the early days of Natal settlement, and in 1848, had been granted a title to some 5,816 acres in that area by the Natal Government in recognition of his services to the Colony. His domain stretched from the Umlaas river to the Umbogintwini river.

After the influx of immigrants between 1849 and 1852 Dick King split up and sold some of this land piecemeal to various newcomers including Messrs Edward Priddle, James Craw, Sydney and Lawrence Platt, Elizabeth Searle, Michael Jeffels, and he further rented portions to Messrs Lamport, Smart, Ansell, Fynn, Joyner, Mack and others, most of whom eventually went in for sugar cane cultivation.

It would seem that William (003) Quested decided to do likewise. Having bought some of Dick King’s land, William and his two young sons settled at Isipingo quite close to Dick King’s homestead.

In those early days it appears to have been considered that only the coastal lands were suitable for sugar cane and because the Questeds eventually became sugar planters it is perhaps worthwhile to recall something of the early history of the sugar industry in Natal.

Before sugar was produced in the Colony the local demand was met by imports from Mauritius, and these were not superseded until well after about 1855, although small amounts of locally made sugar produced from Natal grown cane became available before then, as will be described.

There had always been a semi-indigenous sweet sorghum plant known as ‘imfe’, growing in parts of Natal. The native people chewed it for the sweet juice it contained and it made good cattle fodder, but the sucrose content was considered to be too low for it to have any commercial value.

It is also known that a type of true sugar cane named ‘umoba’ was grown in small quantities around the kraals of certain African chiefs. This is believed to have been introduced by Arab or other Eastern traders of very early days. In 1635, Portuguese sailors were said to have found natives growing sugar cane at the mouth of the Umzimkhulu river where Port Shepstone stands today.

The Zulu king Shaka was said to have worn ear ornaments made from sugar cane, and in July 1847 J.W. Shepstone was shown good yellow sugar said to have been made by Zulus at the Lower Tugela Drift.

In the late 1840’s a number of settlers began to consider the possibilities of growing sugar cane as a commercial proposition along the Natal coastal strip and support for this idea came from various persons who had had previous experience of cane cultivation in Mauritius and in the West Indies. A number of experiments were carried out by people in the late 1840’s and in 1850 a Mr George Marcus, from the West Indies, made a sample quantity of sugar from green cane grown by Africans.

In the late 1840’s a number of settlers began to consider the possibilities of growing sugar cane as a commercial proposition along the Natal coastal strip and support for this idea came from various persons who had had previous experience of cane cultivation in Mauritius and in the West Indies. A number of experiments were carried out by people in the late 1840’s and in 1850 a Mr George Marcus, from the West Indies, made a sample quantity of sugar from green cane grown by Africans.

The Milner brothers of Durban imported seeds and cane tops from Mauritius and the Ilse de Bourbon (Reunion) in 1847, and these were sold by auction to a number of settlers who planted them at various places along the coast. Amongst those planters, and possibly the originator of the scheme, was a certain Edmund Morewood who became the real pioneer producer of locally made sugar in the Colony.

Having obtained his requirements of cane tops, Morewood planted them on his farm Compensation, which was situated between the Tongaat and Umhlali rivers, about 30 miles along the North coast from Durban. Here, assisted by George Lamond and by some men from Mauritius, he carried out systematic experiments in cane cultivation, and by 1850 he had planted up about six acres of cane, soon to be increased to 40 acres. He then constructed a simple type of crusher mill, using rollers reputedly made from a ships mast, about 14 inches in diameter. It seems the machine was something similar to an old-fashioned mangle, except that the rollers were vertical. Cane was fed by hand between the rollers and the mill was turned by four native pushing long wooden arms while walking round and round in a circle.

There is in fact some disagreement about what his first mill really was like. A number of people said it had wooden rollers, as described, and this was backed up by the notary J.D. Shuter. He stated that he had been interested to see Morewood’s primitive mill in which the cane was crushed by wooden rollers cut from a ships mast, but some years later, after he had left the Colony, Morewood stated that his mill had had iron rollers. It seems more likely that he was thinking about his second mill when he said this.

The juice squeezed out from the cane was collected in wooden guttering leading to the boiling pots. The mill produced about 12 gallons of juice an hour. After screening to remove solid matter and adding milk of lime to clarify it, the juice was boiled in what were, in fact, nothing but large kaffir cooking pots. When boiled, the resulting syrup was filled into porous containers to drain and separate the molasses from the sugar, after which the partially crystallised sugar was spread on flat surfaces, exposed to the sun to dry and to complete the crystallisation process. 100 gallons of juice gave about 110 pounds of sugar and about 60 pounds of molasses.

In this manner was the first factory-made sugar produced in Natal by Morewood when he reaped his first cane crop in the year 1851. Samples of his cane and sugar were exhibited in Durban in January 1852 and at the Pietermaritzburg Agricultural Society Show later in the year. A shop known as Jaques Store in Durban was selling sugar from Morewood’s mill that same year at 4½d a pound.

Because Morewood’s boiling pots were housed in a brick-built, iron-roofed shed erected for the purpose, his was rightly regarded as the parent sugar factory in Natal and indeed, in the whole of South Africa.

In the light of experience gained, Morewood had an improved and larger mill constructed of cast iron, and used oxen as motive power.

Soon after this initial success, scores of interested visitors made the way to Compensation Estate, some to offer Morewood advice for possible improvements to the milling and boiling plant, but others to learn from him how to cultivate cane and how to process the ripe cane into sugar. Cane tops from Morewood’s fields were bought by many people and further supplies were imported from Mauritius by Messrs Henderson, Smerdon and Co. in 1852. Cane tops of a different variety were imported from Penang by Mr J. Leyland Fielden in December 1852.

In a very short while a number of settlers had got cane planted on their lands and were busy constructing home-made mills. The rush had started and all who could climbed aboard the band-wagon.

Michael Jeffels and the brothers Sydney and Lawrence Platt appear to have been the pioneers of sugar cane planting at Isipingo. In 1852 several farmers from that district went to Compensation Estate in their ox-wagons to buy cane tops from Morewood. They paid £3 per thousand for four different varieties of cane and it was from these cuttings that a number of sugar estates at Isipingo were started. By 1853, the Platt brothers, William Joyner, Dick King, the Dennils, Robert Babbs, Atkinson and Priddle were all growing cane on a small scale at Isipingo, while Edward Lamport had established a plantation in the adjacent area of Merebank. This district quickly became the centre of the sugar industry in Natal.

Most planters made their own simple crusher mills on the lines of Morewood’s original one, but no doubt incorporated some of their own ideas and they used oxen, mules or donkeys to drive the mills.

Michael Jeffels of the Albion Estate was considered the first large-scale cultivator of cane in Natal. He installed the first imported crushing machinery and boiling pans, shipped out from Great Britain in July 1853, but this was still a very simple plant with a relatively small output. Jeffels had the distinction of being the first planter to have bulk supplies of sugar, in hogsheads of ¼ ton each, sold on the Durban market, and his estate was said to be in many respects the estate ‘par excellence’ on the Isipingo. The first real commercial quantities of sugar were not produced until 1855 when some eight tons were sold at £30 a ton by Mr Acutt, the auctioneer, at the Durban market on 23rd June, some of this coming from Milner and Miller’s Springfield Estate near the Umgeni river on the northern side of Durban, but the greater part of the cane juice processed at Springfield had in fact come from the estates of Messrs Jeffels and Joyner of Isipingo. The sugar produced by the Springfield mill, which had installed a centrifugal machine in 1855, was said to be equal to the finest qualities from Mauritius.

From 1855 onwards regular sales of sugar were held at the Durban market and in 1860 some 250 tons of Natal sugar were shipped to England in the Henrietta, thus establishing the Colony as a sugar exporting country.

Steam power for driving cane crusher mills was first employed in by Jeffels in 1856 and by the end of that year Joyner, King and various others had also put in steam engines. About the same time iron rollers for crushing the cane were put into more general use, together with other improvements in production methods, and most of the sugar then manufactured was of a large-grained golden-yellow variety, similar to Demerara.

By 1857 there were about 476 acres of cane under cultivation and nine mills in operation in the Isipingo area well before William and George Quested started their plantations. Five years later it was estimated that there were about 3,190 acres under cane and 37 mills in Natal, either already in operation or nearly ready to start. By 1864 there were 11 mills working at Isipingo, and by 1867 the number of mills had increased to 15. The Quested’s mill must have been included in this number. Throughout Natal the industry continued to grow so that by 1869 there were about 5,757 acres of growing cane and a little later, during the 1870/71 season, sugar production amounted to approximately 8,000 tons, an enormous increase as the industry got into it’s stride.

Lack of efficient transport proved a great handicap to planters all the way along and this situation persisted until about 1880. Another problem was the lack of suitable labour for the cane fields and mills. Zulus were not keen to work on the land and to many planters African labour appeared to be unreliable and inefficient. It was for this reason that the Natal Government agreed to the introduction of Indian coolie labour in the 1860’s, but it is of interest to note that some planters had no trouble at all with African labourers and they employed no Indians. There is little doubt that the use of Indian coolies, together with the advent of the railway from Durban to Isipingo in January 1880, were the two factors which resulted in major improvements to the general situation and enabled development to go ahead at a faster pace.

In 1875 approximately 10,000 tons of sugar were made in Natal, this having been produced by 55 steam-driven mills and nine mills operated by horses or oxen. The average yield at this time was said to be about 1 1/3 tons of sugar per acre of cane and the selling price of manufactured sugar was between £17 and £19 a ton. As a by-product, about 40,000 gallons of rum were distilled during the year. Where this enormous amount of liquor was consumed is not clear. Perhaps some of it was exported, but it is likely that a fair proportion was transported over the Drakensberg to the diamond fields at Kimberley and the Vaal.

Severe drought at the end of 1878 and a depression in the industry in 1879 due to the Zulu war had it’s effects and planters suffered accordingly. Other setbacks over the years were encountered caused by frosts, runaway fires, floods and diseases in the canes then in use. Of these, disease was the most important problem and to counter it several new types of cane were introduced from other parts of the world. Some were satisfactory but some were not. New strains developed in Natal itself later proved to be the answer and the earlier types of cane were eventually eliminated.

Some planters borrowed excessively to finance the setting up of milling machinery, obtaining three years credit at 8% to 12%, and a number of them went under, their estates and mills reverting to the mortgagees.

In 1877/78 there were 74 mills operating in Natal but by the year 1884 this number had dropped to 44.

It is clear that the sugar industry was established well before the Questeds became involved in it and they were, therefore able to benefit to some extent from the experience of the earlier pioneers. There is little doubt, however, that they suffered from the same sort of setbacks as the other planters from time to time, but it is known that William Quested, over a period of more than 20 years, developed a well run estate and an efficient sugar mill.